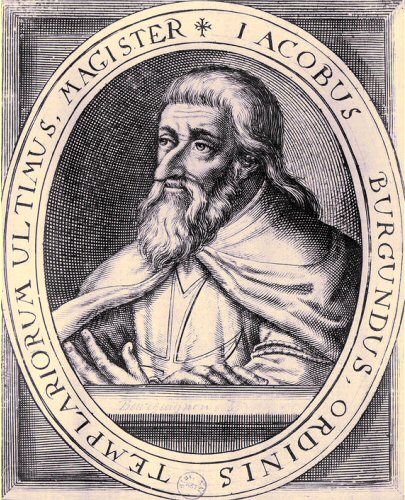

This Masonic legend, mostly told in the Swedish Rite lodges, is a curious variation of stories surrounding the final days of Jacques de Molay. The core of the legend is found in the so-called Strasbourg Manuscript, dating around 1760. The document is in French, although there are some indications that this was not the author’s native tongue. Carl Friedrich Eckleff (1723-1786), the originator of the Swedish Rite, is most likely connected to this document in some way. The manuscript is somewhat oddly entitled Deuxième Section, de la Maçonnerie parmi les Chrétiens (“Section 2, Masonry among the Christians”) and I will probably publish it as a curiosity at a later point. There are some additional later details for which I am mostly following Allgemeines Handbuch der Freimaurerei, by C. Lenning.

This Masonic legend, mostly told in the Swedish Rite lodges, is a curious variation of stories surrounding the final days of Jacques de Molay. The core of the legend is found in the so-called Strasbourg Manuscript, dating around 1760. The document is in French, although there are some indications that this was not the author’s native tongue. Carl Friedrich Eckleff (1723-1786), the originator of the Swedish Rite, is most likely connected to this document in some way. The manuscript is somewhat oddly entitled Deuxième Section, de la Maçonnerie parmi les Chrétiens (“Section 2, Masonry among the Christians”) and I will probably publish it as a curiosity at a later point. There are some additional later details for which I am mostly following Allgemeines Handbuch der Freimaurerei, by C. Lenning.

When Jacques de Molay became certain that his days were numbered, he arranged for his nephew, one count de Beaujeu, to visit him in prison. The Grandmaster had previously noted this young man as someone who could be trusted with the task of keeping the Order of the Knights Templar alive. De Molay instructed his nephew to go down to the crypt in which prior grandmasters of the Order were buried. There, underneath one of the coffins, de Beaujeu was to find a crystal box encased in silver and bring it back to the Grandmaster. The young man followed these directions and returned with the crystal box. De Molay was well pleased with his nephew’s loyalty and made him swear an oath, promising to do whatever it takes to preserve the Order until the day of the Last Judgement. It also turned out that the crystal box that had been retrieved from the crypt contained a precious relic, once given to the Knights Templar by King Baldwin of Jerusalem — the right index finger of John the Baptist.

Jacques de Molay further instructed his protege, giving him keys that offered complete access to the treasures of the Knights Templar. Most of them were concealed in the very same coffin under which the crystal box had been hidden. Among these treasures were ancient documents, the crown of the kings of Jerusalem, a golden seven-branched candelabrum and golden figures of the four gospel writers, once part of the decor at the Holy Sepulchre. The only way Jacques de Molay could transport these treasures to Paris was in the coffin, supposedly containing the body of Guillaume de Beaujeu, Templar Grandmaster who died during the siege of Acre. It so happened that count de Beaujeu was also related to Guillaume de Beaujeu. De Molay further revealed that the crypt’s columns were hollow and contained immense amounts of money. This money was to be used for the purposes of keeping the Order alive.

It is also added that when Jacques de Molay was executed at the stake he was only partially burned. Count de Beaujeu along with 9 men he had recruited was able to take the Grandmaster’s body and place it in the coffin containing the Order’s treasures. As a blood relative of Guillaume de Beaujeu, the young count petitioned the king for permission to transfer the coffin out of the crypt. This was granted and the newly restored Order could now relocate its precious relics to safety freely.

One particularly curious episode, not found in the Strasbourg Manuscript, relates how de Beaujeu and his friends came across the funeral procession of Clement V (his body also had to be transfered a great distance). At night, they replaced the body of the Pope with that of Jacques de Molay and started a fire to cause confusion. The body of Clement V was then burned in an open field and his ashes were scattered on the wind. Ironically, the body of the last Grandmaster of the Knights Templar was properly buried with all possible honors. Only later de Beaujeu reburied de Molay once more, for the final time, under a plaque that says: JBMBADNJC MCCCXIV. 11 Mart (Jacobus Molay Burgundicus Bustus Anno Domini Jesu Christi 1314, 11 Mart.)

This odd legend hardly requires any debunking in terms of historical veracity. It is just important to note, that the Strasbourg Manuscript is sometimes presumed to be a primary source. This is quite erroneous, because this document is far removed from the early 14th century and its provenance is not completely certain even in that reduced capacity. Of course, any symbolic meaning that one can find in this legend is in no way diminished as a result.

You may be interested in these blog posts:

Important document about the Templar treasure

Famous Knights Templar

Very interesting!